Introduction

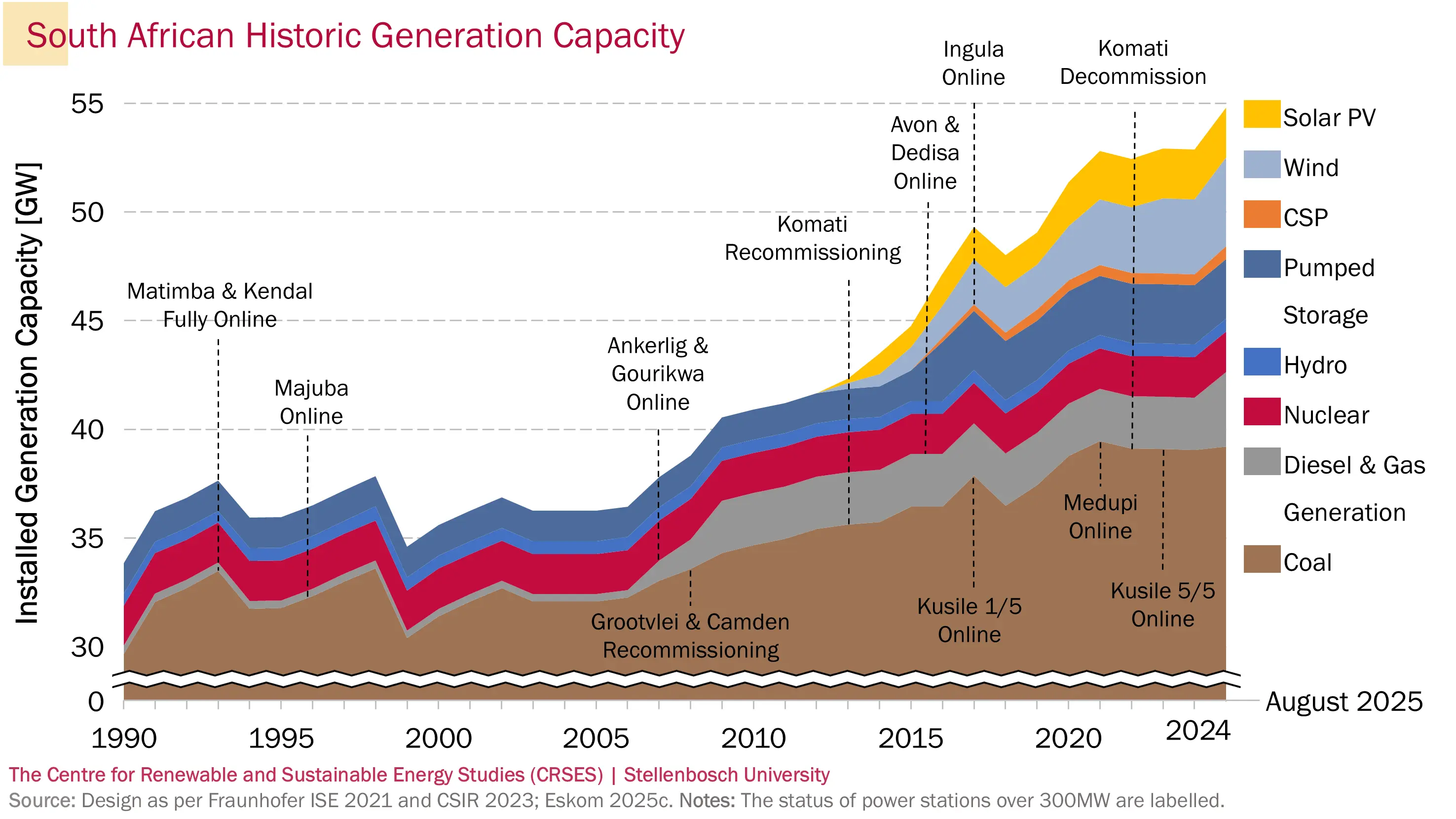

South Africa’s energy sector stands at a crossroads in 2025, characterized by heavy reliance on coal for electricity generation, which accounts for 81% of the mix, while low-carbon sources like solar (9%), wind (5%), and nuclear (3.5%) make up nearly 18% [1]. This dominance persists despite environmental concerns and international commitments to decarbonization, as highlighted in the OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2025, which notes insufficient progress in renewables to meet emission targets [2]. Recent improvements in Eskom’s coal fleet, with an energy availability factor (EAF) peaking at 70% in 2024, have reduced loadshedding, but total electricity demand fell 3% that year, reflecting economic strains and rising tariffs [3]. The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2023) projects coal capacity rising to 39.4 GW by 2030, even as renewable targets are scaled back to 25.7 GW [2]. Amid these dynamics, private sector distributed generation has surged, projected to reach 11.3 GW by 2030, offering a buffer against grid instability [2][3]. This overview sets the stage for examining coal’s grip, renewable growth, and the path forward.

Coal’s Enduring Dominance and Challenges

Coal remains the backbone of South Africa’s energy mix, powering major stations like Medupi and Kusile (each 4,800 MW), alongside Kendal, Majuba, and Lethabo [1][3]. In 2024, coal-generated energy increased due to better plant availability, yet the sector’s CO₂ emissions continue to dominate, exacerbating climate impacts [2][3]. The CSIR Utility Statistics Report for January 2025 reveals that while Eskom’s EAF improved from 59.92% in 2023, no new utility-scale capacity was added, underscoring reliance on existing infrastructure [3].

Expert analyses point to economic and political barriers sustaining this dominance. The OECD report criticizes the IRP 2023 for not planning coal plant closures, instead prioritizing completions like Kusile’s Unit 6 in September 2025, which boosted capacity but overran budgets significantly [2]. Social media reflects public frustration, with users highlighting coal’s cost-effectiveness per kWh versus renewables’ higher rates, often labeling the latter as inefficient despite investments. However, NGOs emphasize health costs in Mpumalanga, where pollution affects low-income communities, advocating for phased decommissioning.

Renewable Energy Growth and Technological Innovations

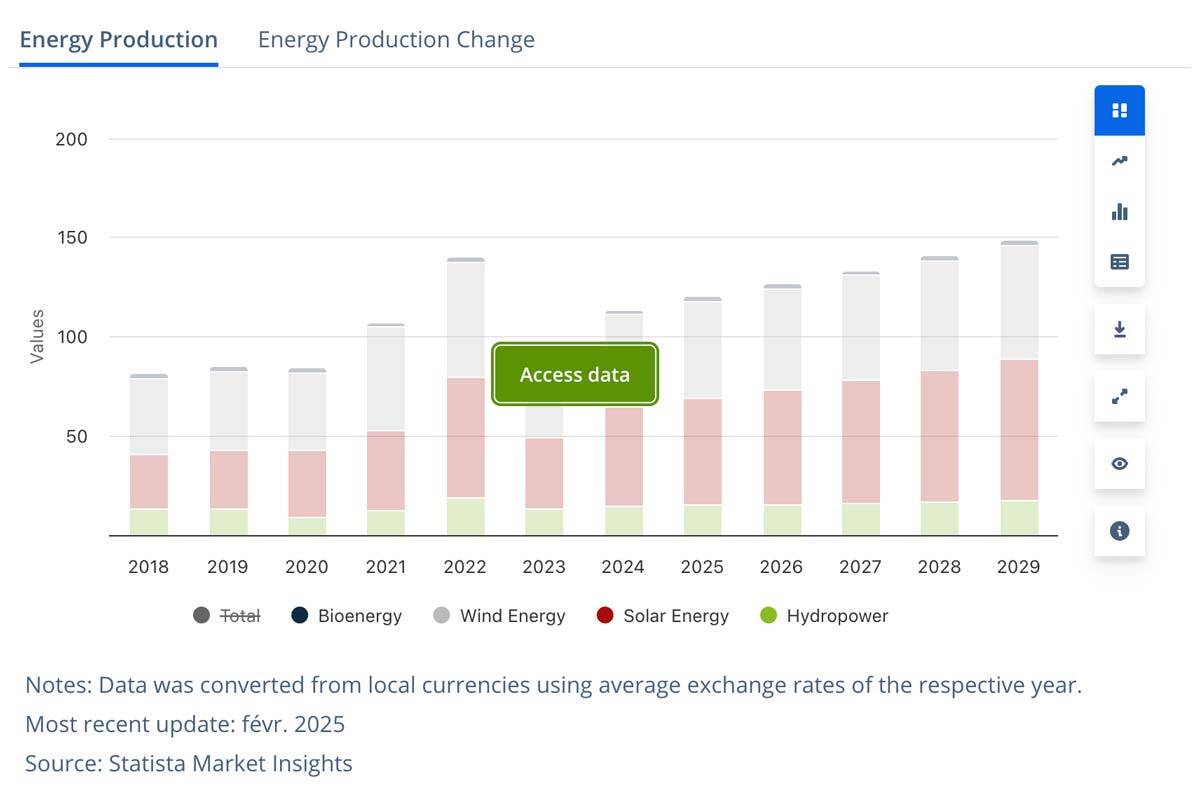

Renewable capacity is growing modestly, driven by the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP), which focuses on solar and wind in resource-rich areas like the Northern Cape [4]. By 2030, total renewables are projected at 25.7 GW, with distributed generation jumping from 4.5 GW to 11.3 GW, reducing peak demand by 1% in 2024 [2][3]. Innovations include battery storage projects worth 7 billion rand and flexible power purchase agreements shifting toward merchant models.

Expert commentary highlights hybrid models as a trend. Technological advancements in gas turbines and LNG could potentially displace Eskom supply by 2027. Yet, challenges like grid variability and high costs persist, with solar and wind contributing only 14% despite potential [2].

Policy Frameworks and Socioeconomic Impacts

Policies like IRP 2023 emphasize energy security, expanding nuclear by 9.6 GW and gas infrastructure, but reduce renewable targets from prior plans [2][4]. Tariff hikes—190% since 2014, with 12.74% in 2024/2025—drive private adoption but strain affordability [3]. NERSA’s approvals aim to bolster Eskom’s finances.

Balanced perspectives reveal tensions: the Just Energy Transition Partnership plans nine coal plant closures by 2030, risking jobs in Mpumalanga, yet promises equitable shifts. Expert opinions warn of corruption in projects like Kusile, urging transparent reforms. OECD recommends market restructuring to integrate privates and strengthen grids [2]. Constructive solutions include “just hybrid zones,” retrofitting coal plants with carbon capture alongside solar farms to create jobs and cut emissions gradually.

Emerging Trends and Solutions

Trends in 2025 show diversification: Anthem’s launch for renewables and ExxonMobil’s LNG pursuits signal investment. Eskom’s R320 billion plan adds 5.9 GW clean capacity by 2030. Solutions under study include nuclear expansion for baseload stability and gas as a bridge fuel [4].

Viewpoints vary: some favor ideology-free rationality, prioritizing cheap nuclear over “expensive” renewables. NGOs push for inclusive planning to mitigate inequities. Original insights suggest hybrid models could avoid stranded assets, funding innovations via Eskom profits.

Key Figures

- Coal share in electricity generation (2024/2025): 81% of South Africa’s electricity comes from coal, with low-carbon sources (solar, wind, nuclear) making up nearly 18% (solar ~9%, wind ~5%, nuclear ~3.5%)[1].

- Per capita electricity consumption: Dropped to 3,647 kWh per person in 2025, down from a peak of 5,214 kWh in 2007[1].

- Coal capacity projections: The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2023) projects coal capacity will increase to 39.4 GW by 2030 (up from 33.4 GW in IRP 2019)[2].

- Renewable capacity projections: Total renewable capacity is projected at 25.7 GW by 2030 (down from 31.1 GW in IRP 2019), with distributed generation rising from 4.5 GW to 11.3 GW[2].

- Electricity tariffs: Average national tariff increased by 190% since 2014; granted increases include 12.74% for 2024/2025[3].

- Large coal power stations: Medupi and Kusile each have a capacity of around 4,800 MW; other major plants include Kendal, Majuba, and Lethabo[1][3].

- Energy demand: Total electricity demand declined by 3% in 2024 compared to 2023, with peak demand 1% lower year-on-year[3].

- Energy availability factor (EAF): Eskom’s coal fleet EAF improved to a weekly peak of 70% in 2024, up from 59.92% in 2023[3].

- CO₂ emissions: The electricity sector remains a major emitter due to coal dominance[2].

Recent News

- Loadshedding: Despite record loadshedding in 2023, improvements in Eskom’s coal fleet performance minimized loadshedding in 2024[3].

- Tariff increases: NERSA approved a 12.74% tariff increase for 2024/2025, with further increases planned for subsequent years, impacting affordability[3][5].

- Renewable energy growth: Renewable energy installed capacity and production are increasing, but remain a small share of the total mix[4].

- Private sector embedded generation: Rapid growth in private sector embedded (distributed) generation is contributing to reduced peak demand[3].

- No new utility-scale capacity: No new generation capacity was added by Eskom or REIPPs in 2024[3].

Studies and Reports

- OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2025: Highlights that coal remains the dominant energy source (80% of generation) and that progress in renewables is insufficient to meet decarbonization goals. The IRP 2023 does not plan for coal plant closures, instead focusing on completing ongoing coal projects, which may delay emission targets[2].

- CSIR Utility Statistics Report (Jan 2025): Details improvements in Eskom’s coal fleet performance, declining electricity demand, and the impact of rising tariffs. Notes that energy generated from coal increased due to better plant availability, while renewable energy contribution was marginally lower in 2024 than 2023[3].

- CRSES SA Electricity Made Visual: Emphasizes the urgent need for renewable energy adoption due to environmental and economic risks of coal reliance. Notes that renewable energy policies (e.g., REIPPPP) are driving growth in solar and wind, but costs and variability remain challenges, especially for concentrating solar power (CSP)[4].

- SolarAfrica 2025 Energy Trends: Identifies rising electricity tariffs as a key driver for renewable energy adoption, with a shift toward more flexible, shorter-term power purchase agreements in the private sector[5].

Technological Developments

- Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP): Continues to drive utility-scale wind and solar PV projects, selected based on lowest cost per unit of energy, with geographic focus on areas of highest wind and solar resources[4].

- Distributed generation: Significant growth in private, embedded generation capacity (projected to rise from 4.5 GW to 11.3 GW by 2030), reducing grid demand and enhancing energy security[2].

- Nuclear expansion: Government plans to expand nuclear capacity by 9.6 GW over the next two decades as part of a diversified energy strategy[4].

- Gas power: Development of combined cycle gas turbines and LNG projects to provide cleaner, more reliable baseload power[4].

- Flexible power contracts: Growing demand for shorter-term, more flexible agreements with independent power producers (IPPs), moving toward a merchant market model[5].

Regulations and Policies

- Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2023): Current draft emphasizes energy security, maintaining and expanding coal capacity, while reducing renewable energy targets compared to previous plans. Focuses on distributed generation and a gradual transition to a more diversified mix[2].

- Renewable Energy Procurement: REIPPPP remains a key policy tool, but recent bid windows have not significantly increased total renewable capacity[4].

- Tariff regulation: NERSA continues to approve above-inflation tariff increases to support Eskom’s financial sustainability, impacting energy affordability[3][5].

- Market restructuring: Proposals to open the electricity distribution segment to private operators and strengthen municipal capacities to support decarbonization and long-term energy security[2].

Ongoing Projects and Initiatives

- Coal plant completion: Ongoing construction and commissioning of large coal plants (Medupi, Kusile) to maintain baseload capacity[2].

- Renewable energy projects: Continued rollout of solar and wind farms under REIPPPP, though at a slower pace than previously projected[4].

- Nuclear expansion: Planning for significant new nuclear capacity by 2040[4].

- Gas power development: Investment in gas-fired power plants, including LNG import terminals and combined cycle plants[4].

- Private sector embedded generation: Rapid adoption of rooftop solar and other distributed generation technologies by businesses and households, reducing grid dependence[3].

MAIN SOURCES:

- statista.com/outlook/io/energy/renewable-energy/south-africa/ – Statista’s renewable energy market outlook for South Africa (reference for broader context)[6].

This synthesis reflects the most current, reliable data and analysis available as of mid-2025, highlighting South Africa’s ongoing reliance on coal, modest but growing renewable energy share, and the complex interplay of policy, economics, and technology shaping its energy future.

Propaganda Risk Analysis

Score: 7/10 (Confidence: medium)

Key Findings

Corporate Interests Identified

The article mentions entities like ‘Renewable Energy’ (likely referring to programs or companies in solar/wind), ‘Just Energy’ (possibly the Just Energy Transition Partnership), and innovations in battery storage and carbon capture for coal plants. Companies potentially benefiting include coal operators like Glencore (recently inked a 20-year renewable deal to ‘green’ their South African coal ops, per web news) and renewables firms like Discovery Green. This could reflect influence from coal giants seeking to greenwash continued operations via carbon capture retrofits, while renewables companies gain from transition funding.

Missing Perspectives

The article excludes voices from environmental activists, labor unions in coal regions (e.g., concerns about job losses in Mpumalanga, as noted in Guardian articles), and experts critiquing carbon capture as ineffective or a delay tactic for phasing out coal. No mention of opposing viewpoints on the slow pace of transition or environmental impacts like water usage in coal retrofits and intermittency issues with solar/wind.

Claims Requiring Verification

The article lacks specific statistics, but vague references to ‘innovations’ in battery storage, solar/wind focus, and coal retrofitting with carbon capture are presented without sources or data. For context, web results cite real figures like 74% coal reliance in 2021 and pledges of R218 billion, but the article doesn’t verify or cite anything, making claims dubious. No evidence for effectiveness of retrofitting in reducing emissions at scale.

Social Media Analysis

X/Twitter posts on South Africa’s 2025 energy mix reveal diverse sentiments, with some users highlighting renewables overtaking coal globally (e.g., IEA projections) and local stats (e.g., 81.4% coal, 8.1% solar in 2024). Discussions include cost comparisons favoring solar/wind over ‘clean coal,’ warnings of painful transitions, and calls for balanced approaches. No signs of paid promotions or astroturfing; posts are mostly from individuals, with views ranging from pro-renewable optimism to coal defense. Recent activity notes deals like Sibanye-Stillwater’s renewable pipeline displacing Eskom coal supply, but nothing coordinated.

Warning Signs

- Excessive repetition of promotional phrases like ‘Renewable Energy’ and ‘solar and wind’ without critical analysis, sounding like marketing copy

- Missing environmental concerns, such as coal’s ongoing pollution or carbon capture’s high costs and limited efficacy (e.g., no discussion of failures in similar projects)

- Absence of independent expert opinions; focuses on positive ‘innovations’ without balancing with challenges like grid instability or economic impacts on coal-dependent communities

- Potential greenwashing: Portrays coal retrofitting with carbon capture as a seamless ‘transition’ alongside renewables, ignoring criticisms that this prolongs fossil fuel use

Reader Guidance

Analysis performed using: Grok real-time X/Twitter analysis with propaganda detection

Other references :

lowcarbonpower.org – South Africa Electricity Generation Mix 2024/2025

oecd.org – OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2025

csir.co.za – [PDF] Utility-scale power generation statistics in South Africa – CSIR |

crses.sun.ac.za – SA Electricity Made Visual – CRSES | The Centre for Renewable and …

solarafrica.com – 2025 Energy Trends: Renewable Innovations in RSA| SolarAfrica

statista.com – Renewable Energy – South Africa | Statista Market Forecast

rff.org – Global Energy Outlook 2025: Headwinds and Tailwinds in the …

reuters.com – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

oecd.org – Source

wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com – Source

lrs.org.za – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

africanmining.co.za – Source

esi-africa.com – Source

greenbuildingafrica.co.za – Source

ecofinagency.com – Source

furtherafrica.com – Source

globenewswire.com – Source

centralnews.co.za – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source