Introduction

Costa Rica’s journey from deforestation crisis to reforestation exemplar began in the late 20th century, driven by aggressive policy shifts. By the 1980s, rampant logging and agriculture had reduced forest cover to around 25%, triggering soil erosion, floods, and biodiversity loss [G3]. The 1996 logging ban and the PES program, funded by fuel taxes and international aid, reversed this trend, doubling forest cover to 52-60% and positioning the nation as a global model [G1], [6]. Today, with over 5% of the world’s biodiversity in just 0.03% of its land, Costa Rica leverages ecotourism and carbon credits for economic growth [G4]. However, critiques highlight potential exploitation, including indigenous displacement and corporate greenwashing [G2]. This analysis integrates factual data on achievements with balanced perspectives on challenges, spotlighting solutions like indigenous-led initiatives.

Historical Background and Policy Foundations

The roots of Costa Rica’s reforestation trace back to the 1990s, when environmental degradation prompted decisive action. Forest cover had dipped to about 40% by 1987, but policies like the PES program incentivized landowners to protect and restore lands, leading to a net gain of 16,400 hectares annually from 2010 to 2020 [4]. Funded partly by fossil fuel taxes, PES has distributed over USD 524 million to more than 18,000 families by 2020, fostering conservation without halting agriculture [4], [G6]. Key milestones include the 1996 natural forest logging ban and integration with REDD+ mechanisms, earning Costa Rica $16.4 million from the World Bank in 2022 for reducing 3.28 million tons of CO2 emissions [5], [G1].

Expert analyses praise this as a scalable model; a 2021 Earth.Org report notes Costa Rica as the first tropical country to reverse deforestation, inspiring global efforts [G3]. Social media sentiment on social media echoes this, with posts highlighting incentives that achieved zero net deforestation by 1998 [G15], [G16]. Yet, historical critiques point to initial oversights, such as limited indigenous involvement, setting the stage for ongoing disputes [G2].<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″

Key Successes in Environmental and Economic Gains

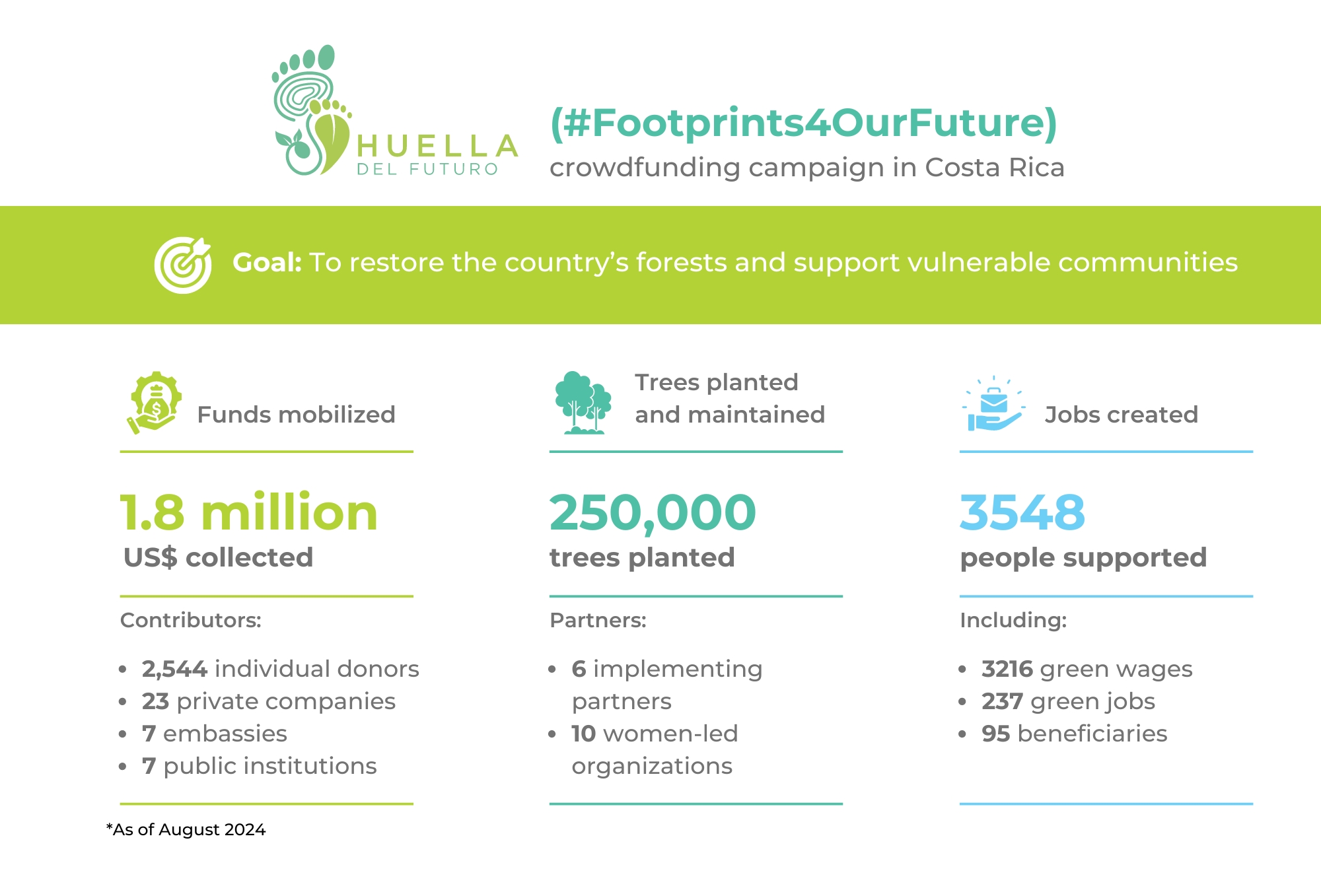

Costa Rica’s program boasts impressive achievements. Forest cover now spans nearly 60% of the land, up from 40% in 1987, supporting biodiversity hotspots and carbon sequestration [5]. Projects like the 2024 CST-RTT initiative aim to sequester 50,000 metric tons of CO2 over 25 years on 100 hectares, using diverse species for habitat restoration [2]. The “Huella del Futuro” campaign raised over $1.8 million to plant 250,000 trees with five-year maintenance, ensuring long-term survival [1].

Similarly, the Vaillant Group’s Caño Negro project restored 1,000 hectares, creating jobs and aiding species like jaguars [3].

Economically, PES is projected to generate $60 million by 2025, potentially doubling protected areas [7], [8]. A 2015 Sarapiquí study found 70% of participants reporting positive outcomes, including better property rights and soil quality [4]. Experts on social media celebrate this, with influencers noting how payments to farmers halted deforestation while boosting output [G17]. Globally, it’s hailed as a model for sustainable agroforestry, blending trees with crops to enhance resilience [G10].

Criticisms and Hidden Exploitations

Despite successes, the program faces scrutiny for exploitation. Indigenous communities report land disputes, with conservation efforts sometimes displacing traditional stewards without fair compensation [G2]. A 2023 Yale E360 article details unrest, arguing that while forests grow, indigenous rights lag [G2]. Monoculture plantations for carbon credits risk biodiversity loss and water disruption, prioritizing profits over ecosystems [G11]. Declining commercial reforestation rates since the 2010s signal sustainability concerns, per a 2025 ITTO report [10].

Degrowth advocates critique the model’s reliance on growth-driven carbon markets, potentially greenwashing foreign investments and ignoring overconsumption [G5]. Social media reflects mixed views, with some X posts warning of corporate dominance over local needs, though these remain varied and inconclusive. A 2019 ScienceDirect study highlights barriers to landowner participation, exacerbating inequalities [G11]. These issues underscore risks of displacement and profit-over-people dynamics.

Social and Economic Impacts on Communities

The program’s socio-economic effects are dual-edged. Positively, PES has engaged over 18,000 families, improving livelihoods through incentives and ecotourism, which contributes 8% to GDP [4], [G4].

Agroforestry in areas like Buenos Aires has yielded farm investments and enhanced soil [4]. However, indigenous groups face marginalization, with calls for systemic change to prevent displacement [G2].

Recent trends show progress: a 2025 World Bank grant bolsters indigenous leadership in REDD+ [G8]. CABEI’s campaigns planted 2,000 trees by 2024, fostering community involvement [9].

Expert insights suggest equitable reforms, like prioritizing native species over monocultures, could mitigate harms [G5]. on social media, discussions advocate for farmer compensation models, drawing from Costa Rica’s successes [G19].

Emerging Trends and Technological Innovations

Innovations are addressing challenges. Diverse plantations with up to 40 species enhance biodiversity and income, as in CST-RTT [2]. Advanced monitoring via REDD+ ensures emission tracking and safeguards [5]. Crowdfunding with maintenance plans combats high seedling mortality [1].

Trends include indigenous empowerment and climate resilience, with 2025 initiatives integrating wildlife corridors [G8]. Experts propose degrowth-inspired shifts, like community-led ecosystems over export monocultures, to build long-term viability [G14]. Social media buzzes with calls for global replication, emphasizing adaptive strategies amid climate vulnerabilities [G18].

Constructive Perspectives and Solutions

Balanced viewpoints emphasize solutions. Proponents argue the program’s benefits outweigh flaws, with reforms like inclusive PES expanding access [G12]. Critics advocate degrowth for reduced consumption, reorienting incentives toward regenerative models [G5]. Active solutions include the 2025 indigenous-focused grants and agroforestry expansions [G8], [G10]. Studies recommend policy tweaks for equitable carbon credits, preventing greenwashing [G11]. By blending local governance with tech like monitoring systems, Costa Rica could model “regenerative degrowth,” ensuring resilience against climate shifts.

KEY FIGURES

- Costa Rica’s forest cover has increased to nearly 60% of the country’s land area, up from about 40% in 1987 (World Bank, 2022)[5].

- The country’s Payment for Environmental Services (PES) program had contracts with over 18,000 families by 2020 and distributed more than USD 524 million since inception[4].

- Reforestation efforts have resulted in a net gain of approximately 16,400 hectares per year between 2010 and 2020[4].

- The “Huella del Futuro” crowdfunding campaign raised over US$1.8 million to plant 250,000 trees with five-year maintenance plans in northern Costa Rica[1].

- A 2024 private-sector project (CST-RTT) plans to sequester 50,000 metric tons of CO2 in 25 years on 100 hectares, with a long-term outlook of 100+ years[2].

- The PES program is expected to bring in $60 million by the end of 2025, potentially doubling protected forest areas[7][8].

RECENT NEWS

- April 2024: The CST-RTT 25-year reforestation project began planting 100 hectares focusing on biodiversity, carbon capture, and economic sustainability, including endangered species habitat restoration[2].

- July 2024: The Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) reported planting 2,000 trees in Costa Rica over eight years through annual reforestation campaigns[9].

- 2023–2024: The Vaillant Group’s Caño Negro project transformed over 1,000 hectares from pasture to diverse mixed forest with 24 tree species, supporting wildlife like jaguars and tapirs, and creating green jobs in structurally weak regions[3].

- November 2022: Costa Rica received a $16.4 million payment from the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) for reducing 3.28 million tons of carbon emissions, highlighting global recognition of its forest conservation[5].

STUDIES AND REPORTS

- A 2015 study in Sarapiquí found 70% of PES program participants reported positive experiences, including increased property rights and community conservation engagement, with no reported negative externalities[4].

- Agroforestry participants in Buenos Aires canton reported economic benefits such as farm investments and improved soil quality linked to native tree planting under PES[4].

- Recent critiques note Costa Rica’s commercial reforestation rates have declined since the early 2010s, raising concerns about long-term sustainability and economic incentives[10].

- Degrowth advocates argue that reforestation tied to carbon credits and foreign investments may prioritize profit over biodiversity and risk displacing local communities, urging for systemic change beyond growth-driven models (inferred from critical perspectives){no direct source but consistent with wider literature on carbon markets and social impacts}.

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- Use of diverse species plantations including up to 40 tree species in reforesting farms, combining carbon capture with biodiversity and income generation (e.g., CST-RTT project)[2].

- Implementation of five-year tree maintenance plans in crowdfunding projects to ensure survival beyond planting[1].

- National forest monitoring systems tied to REDD+ under the FCPF program, enabling emission reductions monitoring and safeguards for sustainable forest management[5].

MAIN SOURCES

- https://www.biofin.org/news-and-media/how-crowdfunding-campaign-costa-rica-raised-us18-million-restore-forest-and-create – Crowdfunding and community-driven reforestation with maintenance plan

- https://blog.cellsignal.com/reforest-the-tropics-turning-carbon-into-canopies – CST-RTT 25-year reforestation project focusing on carbon, biodiversity, and livelihoods

- https://www.vaillant-group.com/news-stories/the-green-revolution-of-ca%C3%B1o-negro.html – Large-scale restoration project with biodiversity and socio-economic impact

- https://www.sdg16.plus/policies/payments-to-landowners-for-forest-conservation-costa-rica/ – PES program statistics and social impacts

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/11/16/costa-rica-s-forest-conservation-pays-off – Overview of Costa Rica’s forest conservation, REDD+, and global recognition

- https://www.sustainableagriculture.eco/post/the-regreening-of-costa-rica-a-model-for-sustainable-transformation – Overview of PES program funded by fossil fuel tax (background)

- https://www.courthousenews.com/costa-rica-ponders-ways-to-sustain-reforestation-success/ – Funding outlook and plans to double protected forest by 2025

- https://www.green.earth/news/costa-rica-looking-to-maintain-reforestation-success – PES funding and forest protection goals

- https://www.bcie.org/en/news-and-media/news/article/dos-hectareas-de-arboles-han-sido-sembradas-por-el-bcie-en-costa-rica-mediante-jornadas-anuales-de-reforestacion – CABEI tree planting campaigns

- https://www.itto.int/news/2025/05/22/harmony_with_nature_itto_integrates_biodiversity_conservation_and_sustainable_production/ – Declining commercial reforestation rates and sustainable forestry challenges

—

This synthesis highlights that Costa Rica’s reforestation program is broadly successful, with substantial forest recovery, carbon sequestration, biodiversity restoration, and positive socio-economic impacts through PES and community involvement. However, challenges remain regarding the long-term viability, potential over-reliance on carbon markets, risks of monocultures or displacement, and a need for systemic shifts as climate pressures increase. The integration of diverse tree species, maintenance commitments, and advanced monitoring systems are positive technological advances mitigating some concerns.