Ecological Footprint: Unseen and Long-lasting

The allure of deep-sea mining is its potential to provide materials with supposedly lower immediate environmental impact compared to terrestrial mining. Yet, data reveals a different scenario. Studies in 2025 have shown that tracks from deep-sea mining operations done decades ago are still visibly disturbed, with minimal signs of biological recovery. The UK’s National Oceanography Centre underscores that ecosystems remain heavily altered even 44 years post-mining (NOC, 2025). This persistent disruption poses severe risks to biodiversity, particularly given the CCZ hosts species 90% of which remain undescribed (Natural History Museum, 2025).

Technological Advancements Versus Ecological Sensitivities

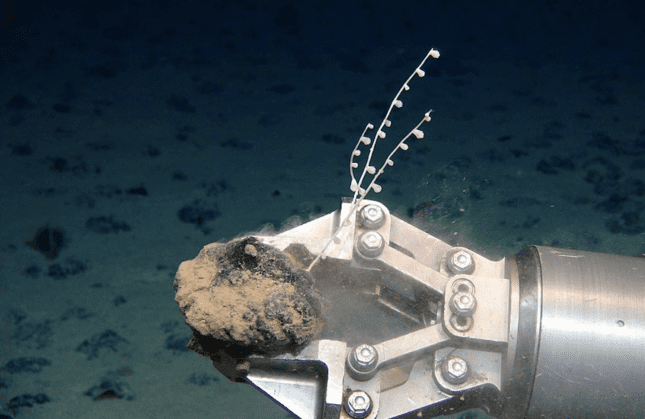

Advancements in technology have introduced modern collector designs purportedly designed to minimize physical damage. Despite these improvements, long-term studies suggest that these newer systems still pose substantial risks to deep-sea ecosystems. Critical analyses advise caution, pointing out that while technological advancements are ongoing, their ecological footprints are yet to be fully understood (BGS & NOC, 2025).

Governance and Transparency Concerns

The governance of deep-sea mining activities by entities such as the International Seabed Authority has been criticized for lack of transparency and potential conflicts of interest. Recent reports advocate for a more robust regulatory framework that ensures environmental protections are not overridden by commercial interests (Earth.Org, August 2025).

Alternatives to Deep-Sea Extraction

As critiques mount against the ecological viability of deep-sea mining, experts and conservationists emphasize alternative pathways such as demand reduction through improved recycling rates and innovations in battery technology that use less impactful materials. These alternatives promise a reduction in reliance on seabed mining while also mitigating other environmental impacts.

KEY FIGURES

- Deep-sea mining tracks in the CCZ remain visibly disturbed 44 years after experimental mining, with an 8-meter-wide cleared strip and large furrows still present (NOC study, 2025)[1].

- Approximately 90% of species in the CCZ are undescribed, indicating extreme biodiversity knowledge gaps (Natural History Museum, 2025)[3][4].

- Some biological populations (e.g., sediment macrofauna, mobile deposit feeders) show early signs of recolonization after 44 years, but ecosystem recovery is incomplete and persistent physical alterations remain (Nature journal, 2025)[1][5].

- Experimental dredge sites in the CCZ show little to no organism recovery even decades after disturbance (IUCN report, 2023)[4].

RECENT NEWS

- March 26, 2025: UK’s National Oceanography Centre published a landmark study in Nature revealing long-term impacts and first biological recovery signs after 44 years in the CCZ post-mining (NOC)[1].

- July 18, 2025: Smithsonian Magazine highlighted growing scientific concern over deep-sea mining’s irreversible effects on biodiversity and slow ecosystem recovery, emphasizing the CCZ as a “scientific black hole” due to insufficient species data (Smithsonian)[3].

- October 26, 2023: IUCN WCPA released a report emphasizing the lack of environmental baseline data and the persistent ecological damage in the CCZ, urging caution before permitting mining (IUCN)[4].

STUDIES AND REPORTS

- Jones et al. (2025, Nature): Mining impacts persist over decadal scales; even after 44 years, physical seabed disturbance remains, though some fauna begin recolonizing. Plume effects appear limited in residual sedimentation, but direct disturbance areas show altered communities. Calls for protected networks and careful management (NOC-led)[1][5].

- Rabone et al. (2023): Biodiversity assessment found 90% of CCZ species undescribed; mining threatens slow-growing, highly endemic species; ecological impacts likely irreversible without mitigation (Natural History Museum)[3].

- BGS and NOC (2025): Sedimentological studies show lasting changes due to historic mining propulsion designs distinct from modern collectors; variable fauna impact but long-term sediment disruption confirmed (BGS)[2].

- IUCN MCWG (2023): Experimental dredging shows minimal recovery decades later; major unknowns remain around species distribution, ecological function, and sediment plume impacts; stresses precautionary principle (IUCN)[4].

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- Modern collector designs in deep-sea mining aim to reduce physical sediment disturbance compared to earlier propulsion-based mining tested in 1979, but long-term ecological footprint remains uncertain (BGS, NOC studies, 2025)[1][2][5].

- Advances in deep-sea monitoring technologies (ROVs, sediment sensors) improve baseline data acquisition but remain insufficient to fully characterize biodiversity and ecosystem functions in the CCZ (Natural History Museum, 2025)[3].

- Life-cycle assessments (LCA) by mining companies claim lower carbon footprints than terrestrial mining, but independent analyses highlight gaps in accounting for biodiversity loss, microbial disruption, and carbon cycle disturbances in abyssal sediments (Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre commentary, 2025)[2].

MAIN SOURCES

- https://noc.ac.uk/news/new-study-reveals-long-term-impacts-deep-sea-mining-first-signs-biological-recovery — UK National Oceanography Centre report on 44-year impact and recovery study in CCZ (2025).

- https://www.bgs.ac.uk/news/new-study-reveals-long-term-effects-of-deep-sea-mining-and-first-signs-of-biological-recovery/ — British Geological Survey sedimentological analysis and impact study (2025).

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/as-interest-in-deep-sea-mining-grows-scientists-raise-alarms-about-the-possible-ecological-consequences-180987009/ — Smithsonian Magazine feature on ecological risks and knowledge gaps (2025).

- https://conservationcorridor.org/ccsg/working-groups/mcwg/mcwg-activities/case-studies/clarionclipperton/ — IUCN WCPA report on CCZ environmental assessment and mining risks (2023).

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08921-3 — Peer-reviewed study in Nature detailing long-term biological recovery in deep-sea mining areas (2025).

Summary: Current scientific evidence from the CCZ shows that despite some early biological recovery signs, deep-sea mining causes persistent physical and ecological damage lasting decades or more, with major unknowns about biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Claims of “sustainable” cobalt and nickel from deep-sea mining are thus not fully substantiated beyond green marketing, given the weak baselines, unproven plume control, and incomplete understanding of long-term impacts. Governance by the International Seabed Authority is under scrutiny for transparency and data gaps. Alternatives such as demand reduction, recycling, and material efficiency are emphasized by experts as critical pathways to reduce reliance on deep-sea extraction.

Other references:

noc.ac.uk – New study reveals long-term impacts of deep-sea mining …

bgs.ac.uk – New study reveals long-term effects of deep-sea mining …

smithsonianmag.com – As Interest in Deep-Sea Mining Grows, Scientists Raise …

conservationcorridor.org – Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) – Environmental …

nature.com – Long-term impact and biological recovery in a deep-sea …

wri.org – Source

earth.org – Source

nature.com – Source

nature.com – Source

planet-tracker.org – Source

iucn.nl – Source

scientificamerican.com – Source

nature.com – Source

smithsonianmag.com – Source

npr.org – Source

cen.acs.org – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

frontiersin.org – Source

oceanminingintel.com – Source

x.com – Source