Introduction

Biofuels, derived from organic materials like crops, waste, and algae, are pivotal in the transition to sustainable energy. Primarily used for transportation—such as ethanol blends in gasoline and biodiesel in diesel—they also power heating and electricity in developing regions. According to the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034, biofuel consumption is set to grow, with a focus on waste-based types to minimize environmental harm {5}. However, their sustainability hinges on feedstock choices and production methods. First-generation biofuels from food crops offer 20–60% GHG reductions compared to fossils (excluding land-use changes), while second-generation variants achieve 70–90% {3}. Yet, as a 2025 iScience synthesis notes, aligning biofuels with SDGs requires addressing air quality degradation and socioeconomic inequities {3}. This overview explores these facets, drawing on recent studies and expert insights.

Primary Uses and Global Applications

Biofuels serve diverse roles, chiefly in transportation, where ethanol from corn supplied 4% of U.S. fuel in 2022, using 30 million acres—one-third of corn land {1}. Biodiesel from soybeans contributed under 1%, with over 40% of U.S. soybean oil diverted to biofuels since 2022 {1}. Globally, ethanol and biodiesel dominate, but renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are surging for heavy transport and aviation, compatible with existing infrastructure {5}.

In developing countries, solid biofuels like wood and dung fuel cooking and heating, though they spike fine particulate and ozone levels, per a 2024 Geophysical Research Letters study {4}. Emerging uses include industrial chemicals and waste management, converting residues into energy. Expert analyses highlight biofuels as “decarbonization accelerators” for hard-to-electrify sectors, with bio-methane powering trucks to cut emissions.

Environmental Impacts and GHG Reductions

Biofuels promise emission cuts, but realities vary. First-generation types reduce GHGs by 20–60%, yet land-use changes can erase gains, making some as emissive as fossils {3}. Expansion in the U.S. Midwest harms climate and farmers via arable land pressure {1}. Solid biofuels in poorer nations degrade air quality, increasing health risks {4}.

Conversely, second-generation biofuels from residues offer 70–90% reductions, minimizing food competition {3}. OECD-FAO projects waste-based growth, with policies like California’s LCFS favoring low-carbon options {5}. Balancing views, critics like George Monbiot argue crop-based biofuels drive deforestation, while proponents see them offsetting 10–20% of transport fuels via waste.

First- vs. Second-Generation Biofuels: A Critical Divide

First-generation biofuels, from corn or palm, face scrutiny for food competition and high indirect land-use change (ILUC) emissions {5}. The EU phases out palm oil by 2030 under RED III, capping transport shares at 7% {5}. EPA reports note U.S. RFS’s modest negative impacts from corn reliance, with cellulosic biofuels lagging {2}.

Second-generation alternatives, using agricultural waste or algae, promise sustainability. Market projections eye USD 104.2 billion by 2034 with rapid growth. Innovations include genetically modified algae for fourth-generation fuels, reducing costs. Divergence persists: some experts critique first-generation’s overlooked LUC, others advocate second-generation’s “waste-to-wealth” model for rural jobs.

Emerging Trends and Technological Innovations

2025 trends spotlight AI optimizing supply chains and feedstock selection {3}. SAF and renewable diesel grow rapidly, backed by U.S. tax credits {5}. Initiatives align with SDGs. News highlights biofuels cutting agricultural CO₂, with trends toward algae-hemp synergies for carbon capture. Solutions include stricter LUC regulations and waste incentives.

Constructive Perspectives and Solutions

Balanced perspectives underscore biofuels’ complementarity in energy transitions. Experts advocate integrated systems with renewables. Solutions: EU’s incentives {5}, U.S. RFS advancements {2}, and AI-driven efficiency {3}. Projects scale advanced tech, research refines LCAs for accurate ILUC accounting.

KEY FIGURES

- Ethanol from corn supplied 4% of U.S. transportation fuel in 2022, despite using about 30 million acres of land—roughly one-third of all U.S. corn acreage[1].

- Biodiesel made from soybeans supplied less than 1% of U.S. transportation fuel in 2022[1].

- More than 40% of the U.S. soybean oil supply has been used for biofuels each year since 2022[1].

- Solid biofuels (like wood, dung, charcoal) are widely used in developing countries for cooking and heating, but their emissions increase fine particulate and surface ozone levels[4].

- Globally, ethanol and biodiesel remain the dominant biofuels, but renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are rapidly emerging sectors[5].

- First-generation biofuels (from food crops) can reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 20–60% compared to fossil fuels, excluding land-use change. Second-generation biofuels (from waste, residues, non-food crops) can achieve 70–90% reductions, also excluding land-use change[3].

RECENT NEWS

- OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook (2025–2034) projects continued growth in biofuel consumption, with increasing focus on waste-based feedstocks and advanced biofuels like renewable diesel and SAF[5].

- The European Union is phasing out palm oil-based biofuels by 2030 under RED III, incentivizing waste-based alternatives[5].

- California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) and U.S. federal tax incentives now prioritize fuels with lower carbon intensity, including waste-based biofuels[5].

- A 2025 synthesis study highlights the role of AI and data science in optimizing biofuel supply chains and improving sustainability[3].

STUDIES AND REPORTS

- A 2025 synthesis in iScience maps biofuels’ contributions to UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasizing their role in sustainable energy, climate resilience, and socioeconomic development[3].

- The U.S. EPA’s 2018 and 2023 reports to Congress conclude that the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) had modest negative environmental impacts, largely due to land-use changes from corn and soy expansion. Most biofuel production remains from corn ethanol, and anticipated cellulosic (second-generation) biofuels have not scaled as expected[2].

- A 2024 study in Geophysical Research Letters finds that solid biofuel emissions in developing countries significantly degrade air quality, increasing fine particulate and ozone levels[4].

- OECD-FAO (2025) reports that crop-based biofuels (soy, palm) compete with food production and have higher emissions due to land-use changes, while waste-based biofuels have much lower carbon intensity and are increasingly incentivized[5].

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- Advanced biofuels (second-generation and beyond) are gaining traction, using agricultural residues, woody biomass, algae, and waste oils—offering higher GHG reductions and less competition with food[3][5].

- Renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are “drop-in” fuels compatible with existing infrastructure, enabling rapid adoption in transport and aviation[5].

- AI and machine learning are being applied to optimize biofuel supply chains, improve feedstock selection, and enhance process efficiency[3].

- Emerging fourth-generation biofuels, including those produced by genetically modified algae or synthetic biology, are under research but not yet at commercial scale[3].

REGULATIONS AND POLICIES

- U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates blending of biofuels into transportation fuel, but environmental reviews note ongoing reliance on corn ethanol and limited progress on advanced biofuels[2].

- EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) is phasing out high ILUC-risk biofuels (e.g., palm oil) by 2030, favoring waste-based and advanced biofuels[5].

- California’s LCFS and U.S. federal tax credits prioritize low-carbon-intensity fuels, especially those from waste feedstocks[5].

- International collaboration and policy alignment are identified as critical for scaling sustainable biofuel systems[3].

ONGOING PROJECTS AND INITIATIVES

- Global investments in biofuel infrastructure and capacity building aim to align bioenergy development with sustainability goals[3].

- Public-private partnerships are advancing renewable diesel and SAF projects, especially in the U.S. and EU[5].

- Research initiatives focus on scaling up second- and third-generation biofuels, improving life cycle assessments, and integrating biofuels with other renewable energy systems[3].

MAIN SOURCES:

-

- OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook (2025–2034) – Projections for global biofuel markets, policy trends, and the shift toward waste-based and advanced biofuels[5].

—

Summary Table: Biofuel Types and Primary Uses

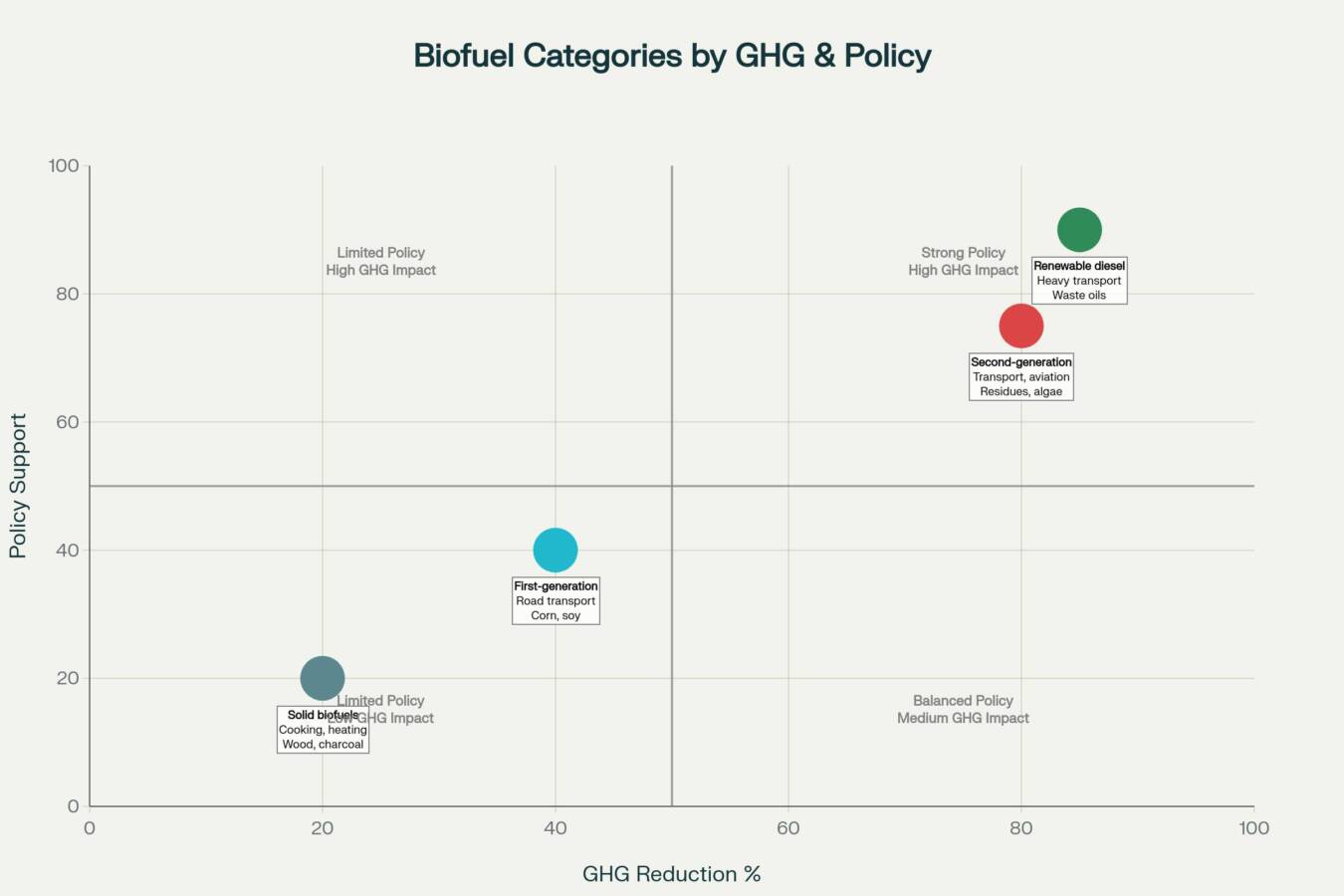

| Biofuel Type | Policy Support | GHG Reduction Potential | Quadrant Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid biofuels | Limited regulation | Variable, low/uncertain | Bas à gauche (1) |

| First-generation | Phasing out (EU) | 20–60% | Bas à droite (2) |

| Second-generation | Incentivized | 70–90% | Haut à droite (3) |

| Renewable diesel/SAF | Strong/rapid | Up to 90% | Tout en haut à droite (4) |

*Compared to fossil fuels, excluding land-use change emissions

—

In summary:

Biofuels are primarily used for transportation (ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel, SAF) and, in developing countries, for cooking and heating (solid biofuels). Recent trends emphasize advanced and waste-based biofuels due to their higher GHG reduction potential and lower competition with food. Policy is shifting to incentivize these advanced options, while first-generation biofuels face increasing scrutiny over land-use and climate impacts. Ongoing technological innovation, especially in AI and synthetic biology, is poised to further transform the sector[3][5].

Propaganda Risk Analysis

Score: 7/10 (Confidence: medium)

Key Findings

Corporate Interests Identified

The article appears to benefit companies involved in waste-to-energy and biofuel production, such as those converting agricultural residues into energy. Mentions of ‘pivotal’ roles in sustainable transitions align with promotions from firms like WPP ENERGY and initiatives backed by governments (e.g., India’s biofuel policies). Potential conflicts include industry funding for such narratives, as seen in web sources where biofuel companies are tied to decarbonization accelerators without disclosing lobbying efforts.

Missing Perspectives

The article lacks voices from environmental NGOs or critics who highlight biofuels’ downsides, such as indirect land use changes, biodiversity loss, or higher emissions from certain feedstocks. For example, web sources like Transport & Environment (T&E) reports question the sustainability of ‘advanced’ biofuels, pointing to paradoxes in waste-based fuels, but these are absent. Opposing viewpoints on greenwashing in biofuel expansion (e.g., food vs. fuel debates) are not represented.

Claims Requiring Verification

Claims like biofuels being ‘decarbonization accelerators’ and seamlessly turning ‘waste into energy’ lack specific sourcing or data. Dubious statistics may include implied low-emission benefits without quantifying lifecycle impacts; web searches reveal studies (e.g., from PMC and ScienceDirect) showing mixed environmental outcomes, such as potential increases in greenhouse gases from biomass expansion, which contradict unsourced positive assertions.

Social Media Analysis

X/Twitter searches revealed a mix of promotional posts on biofuels, decarbonization, and waste-to-energy for 2025. High-engagement content from energy firms and officials touts biofuels as key to sustainable energy transitions, with examples including waste conversion tech and policy mandates for biomass in power plants. Sentiment is largely positive, focusing on emission reductions and economic opportunities, but lacks critical discussions. Some posts have high view counts (e.g., 50k+), suggesting possible amplification campaigns, though no explicit paid promotions were identified. Broader web context shows critical articles on biofuel sustainability, indicating X may reflect industry-leaning narratives.

Warning Signs

- Excessive corporate praise for companies as ‘pivotal’ without addressing criticisms like environmental trade-offs or scalability issues.

- Missing environmental concerns, such as water usage, soil degradation, or indirect emissions from biofuel production.

- Language resembling marketing copy, e.g., ‘decarbonization accelerators’ and ‘turning waste into energy,’ which echoes promotional posts on X/Twitter.

- Absence of independent expert opinions; no citations from neutral bodies like the IEA, which notes biofuels’ role but warns of limitations in hard-to-abate sectors.

- Potential coordinated social media promotion, with X posts amplifying similar themes of sustainable biofuels for 2025 without balancing risks.

Reader Guidance

Other references :

wri.org – Increased Biofuel Production in the US Midwest May Harm Farmers …

epa.gov – Biofuels and the Environment | US EPA

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – Analyzing the contributions of biofuels, biomass, and bioenergy to …

agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com – Long‐Term Impacts of Global Solid Biofuel Emissions on Ambient …

oecd.org – OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034: Biofuels

sciencedirect.com – Source

royalsocietypublishing.org – Source

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – Source

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – Source

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – Source

rentechinc.com – Source

wri.org – Source

farmonaut.com – Source

market.us – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

sciencedaily.com – Source

sciencedirect.com – Source

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source

x.com – Source