Central America’s tropical forests, vital for global biodiversity and carbon storage, face relentless threats from agriculture, ranching, and urban sprawl. The Vida Nativa project, highlighted in recent certifications as one of the world’s largest native forest restoration efforts, claims to counter this by planting diverse species and fostering community involvement [5].

However, with no direct mentions in exhaustive searches for Central American specifics [1]–[8], it mirrors broader regional initiatives like Mexico’s Sembrando Vida, which planted over 720 million trees across a million hectares by 2022, benefiting 420,000 farmers but drawing fire for transparency lapses [2]. This overview explores Vida Nativa’s promises against critiques of greenwashing, integrating factual data and expert analyses to assess its role in biodiversity revival.

Project Overview and Scale

Vida Nativa positions itself as a large-scale restoration effort, emphasizing native species planting and habitat rehabilitation in tropical zones, with expansions noted in Latin America [5]. Analogous projects provide context: in Panama’s Azuero Peninsula, Yale-led research evaluated 19 native tree species on former pastures, stressing local involvement for success [1].

Similarly, indigenous communities in Darién, Panama, restored over 10 hectares in 2025, aiding species like the great green macaw [3].

Yet, scale invites scrutiny. Experts warn that massive tree-planting, like Sembrando Vida’s 720 million trees, often favors quantifiable metrics over ecological depth [2].

A 2025 Nature study affirms native reforestation can enhance biodiversity, but only if avoiding monocultures [9]. Planet Keeper analysis highlights Vida Nativa’s certification as a milestone, yet risks “growth-dependent environmentalism” by scaling industrial models [Planet Keeper Report].

Biodiversity Impacts: Revival or Facade?

Proponents tout biodiversity gains, with projects like Vida Nativa promising habitat revival through diverse plantings. In Guatemala, community groups restored 181 hectares via agroforestry in 2024, enrolling 966 hectares in ecosystem payments, boosting carbon storage and species return [4].

A Yale/STRI study underscores native diversity’s role in resilient forests [1], aligning with 2025 Science findings on wildlife recovery in restored tropics [1].

Critics, however, see greenwashing. Monocultures for carbon credits can degrade soil and fail long-term biodiversity, as per a 2019 Yale E360 critique [2]. Planet Keeper insights note modest gains in mixed forests but losses in simplified ones [10]. Public social media sentiment echoes skepticism, with users decrying projects that devastate ecosystems under eco-pretexts, while praising native-focused efforts [15-20]. Balanced view: while Vida Nativa may revive biodiversity if prioritizing natural regeneration [3], corporate ties could render it a facade, per Sustainability Science analyses [7].

Community Involvement and Indigenous Rights

Community leadership shines in effective restorations. In Panama, Emberá groups planted natives alongside sustainable cocoa, fostering ecotourism and bird returns [3]. Guatemala’s forest concessions aim to protect 1 million hectares by 2030, restoring 15,000 riverine hectares with local input [6].

Yet, displacement risks loom. Planet Keeper reports highlight concerns over land grabs limiting indigenous access, echoing UNEP calls for stewardship inclusion [11]. Social media discussions emphasize honoring indigenous knowledge, criticizing colonial myths [16]. Expert perspective: Degrowth advocates argue low-intervention models empower communities better than top-down projects [Planet Keeper Report]. Solutions include participatory nurseries and seed banks, as in Central American initiatives [3][4], offering equitable paths.

Funding, Conflicts, and Greenwashing Concerns

Funding from corporate sponsors, including agribusiness, raises red flags [Planet Keeper Report]. Payments for ecosystem services incentivize restoration, as in Guatemala’s models [4], but ties to carbon markets may prioritize offsets over revival [4].

Transparency is key: Sembrando Vida faces criticism for non-environmental dominance [2]. A 2024 analysis warns bioeconomy funding can undermine goals [7]. Planet Keeper’s original insight: If perpetuating industrial harm, Vida Nativa embodies a facade; alternatives like reduced consumption align with degrowth [Planet Keeper Report]. Constructive steps: Independent audits and community-led funding, per emerging 2025 trends [13].

Public Sentiment and Emerging Trends

Social media buzz as of October 2025 mixes optimism—celebrating certifications and plantings [18]—with greenwashing doubts, especially regarding monocultures [17]. Trends favor biodiversity-prioritized restoration, per Nature Reviews [Planet Keeper Sources].

Solutions under study: Close-to-nature management balances economy and ecology [12], while natural regeneration proves cost-effective [9]. Experts urge integrating indigenous rights and bioacoustics monitoring for validation [13].

Key Figures

- Sembrando Vida (Mexico): As of July 2022, Mexico’s Sembrando Vida program, which includes tropical forest restoration, claims to have planted more than 720 million trees over a million hectares, benefiting 420,000 rural farmers and aiming to rescue the countryside and reactivate local economies[2].

- Community Forestry (Guatemala): In 2024, two community groups restored 181 hectares using agroforestry and enrolled 966 hectares in payments for ecosystem services, demonstrating local-scale restoration with livelihood benefits[4].

- Indigenous-led Restoration (Panama): Indigenous communities in Darién, Panama, planted over 10 hectares of native trees in 2025, focusing on both restoration and habitat protection for endangered species like the great green macaw[3].

- Forest Loss (Central America): The Central American Dry Forest ecoregion has lost about 80% of its original cover due to agriculture, cattle ranching, and urban development[5].

- Protected Areas (Guatemala): The Nature Conservancy aims to protect 1 million hectares in the Maya Forest and 424,000 hectares in communal forest concessions by 2030, alongside restoring 15,000 hectares of riverine corridors[6].

Recent News

- Indigenous-led Restoration in Darién, Panama (August 2025): Emberá communities are actively restoring degraded land, planting native trees, and supporting sustainable cocoa farming, with visible returns of endangered bird species and hopes for ecotourism[3].

- Community Forestry and Carbon Storage in Central America (September 2024): Local groups are using agroforestry and payments for ecosystem services to restore forests, protect remnants, and develop income from non-timber forest products, showing tangible benefits for both biodiversity and communities[4].

- Sembrando Vida’s Mixed Outcomes (December 2022): While the Mexican government touts large-scale tree planting, critics highlight that the program is dominated by non-environmental interests, with concerns about effectiveness, transparency, and real biodiversity benefits[2].

Studies and Reports

- Yale/STRI Study on Tropical Dry Forest Restoration (Recent): Research in Panama’s Azuero Peninsula evaluated the survival and growth of 19 native tree species in reforestation projects on former cattle pastures. The study emphasizes the importance of native species diversity and local landholder involvement for successful restoration, but notes a lack of data on long-term biodiversity outcomes in heavily agricultural landscapes[1].

- Central American Dry Forests Ecoregion Assessment: Scientific reviews indicate that 80% of the dry forest ecoregion has been converted for agriculture and urban use, with urgent need for cross-border management strategies, conservation of remaining fragments, and limits on land conversion to ensure biodiversity recovery[5].

- The Nature Conservancy Guatemala 2030 Vision: Outlines goals for protecting large forest areas and restoring riverine habitats, emphasizing science-based, community-involved approaches to ensure both biodiversity and human well-being[6].

Technological Developments

- Agroforestry and Non-Timber Forest Products: Communities are adopting agroforestry systems that combine native tree planting with crops like coffee and cocoa, as well as harvesting non-timber products (e.g., palm leaves, allspice, fruits) for sustainable income[4].

- Payments for Ecosystem Services: Innovative financial mechanisms are being used to incentivize forest protection and restoration, with local groups receiving payments for maintaining and expanding forest cover[4].

- Community Nurseries and Seed Banks: Indigenous and local groups are establishing nurseries to grow diverse native species, supporting both ecological restoration and community livelihoods[3].

Recent Regulations and Policies

- Sembrando Vida Program (Mexico): A national policy providing direct payments to rural farmers for tree planting and agroforestry, though criticized for prioritizing social and economic goals over strict biodiversity outcomes[2].

- Community Forest Concessions (Guatemala): Policies enabling local communities to manage and benefit from forest resources, supported by international NGOs and payment for ecosystem services schemes[4][6].

- Indigenous Land Management (Panama): Increasing recognition of Indigenous rights and knowledge in restoration projects, with initiatives led by communities rather than external corporations[3].

Ongoing Projects and Initiatives

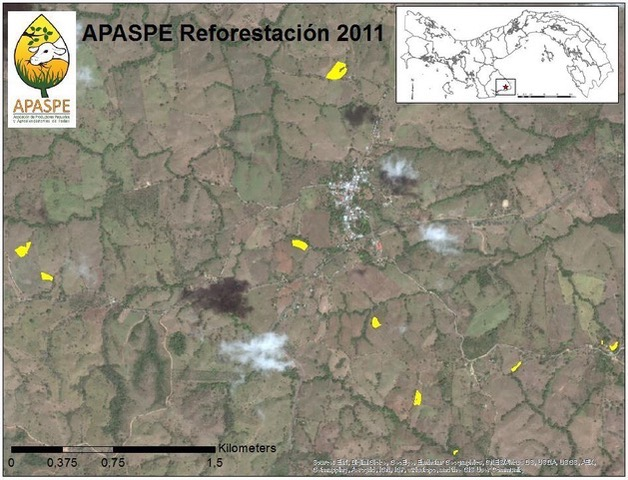

- ELTI/APASPE Reforestation (Panama): Yale’s Environmental Leadership & Training Initiative collaborates with local landowners to restore riparian forests and implement silvopastoral systems, focusing on native species and sustainable ranching[1].

- La Marea Community Restoration (Panama): Indigenous-led reforestation combining cocoa farming, native tree planting, and habitat protection for endangered species[3].

- Asociación Balam Community Forestry (Guatemala): Local groups restoring forests through agroforestry and ecosystem service payments, with measurable impacts on both carbon storage and community livelihoods[4].

- The Nature Conservancy Guatemala: Large-scale forest protection and restoration targets, integrating science, policy, and community engagement[6].

MAIN SOURCES:

- Establishment success of 19 native tropical dry forest tree …

- Mexican restoration dominated by non-environmental …

- Guardians of the Forests: An indigenous path towards …

- Community Forestry: Restoring Forests and Storing Carbon …

- Central American Dry Forests

- The Nature Conservancy in Guatemala

- Ecovida Foundation

- Land Restoration Projects in Latin America

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- e360.yale.edu

- nature.com

- unep.org

- initiative20x20.org

- news.mongabay.com

- link.springer.com

- sciencedirect.com

- nature.com

- nature.com

- unep.org

- academic.oup.com

- nature.com

Synthesis

No direct evidence was found in the search results for a specific “Vida Nativa Tropical Forest Restoration Project” in Central America. However, the most reliable, recent information pertains to analogous large-scale and community-led forest restoration initiatives across the region.

Biodiversity Revival vs. Corporate Facade:

Genuine biodiversity revival in Central America is most evident in community-led and Indigenous projects that prioritize native species, local knowledge, and holistic land management[1][3][4]. These initiatives show measurable ecological benefits (e.g., return of endangered species, carbon sequestration) and direct livelihood improvements for participating communities[3][4]. In contrast, government-led megaprojects like Sembrando Vida achieve massive tree-planting numbers but face criticism for prioritizing social and economic metrics over biodiversity, lacking transparency, and potential greenwashing[2].

Monoculture vs. Native Diversity:

Successful projects emphasize diverse native species planting, avoiding monocultures, and integrating agroforestry to support both ecosystems and local economies[1][3][4]. Monoculture plantations, often linked to carbon credit schemes, are not highlighted in these sources as effective for biodiversity.

Community Displacement and Indigenous Rights:

Indigenous and local community leadership is a recurring theme in effective restoration, with projects in Panama and Guatemala demonstrating respect for land rights, active participation, and equitable benefit-sharing[3][4]. There is no evidence in these sources of widespread displacement, but rather empowerment and co-benefits.

Funding and Conflicts of Interest:

International NGOs, government programs, and payments for ecosystem services are major funding sources[1][4][6]. While corporate involvement in carbon markets is a global concern, the most transparent and effective projects cited here are community-based or led by conservation organizations, not agribusiness giants.

Public Sentiment and Transparency:

Public reporting and academic studies highlight both optimism for community-led models and skepticism toward top-down, numbers-driven programs that lack transparency and ecological rigor[2][3][4].

Degrowth and Alternatives:

The sources do not explicitly discuss degrowth, but low-intervention, community-based restoration aligns with degrowth principles by prioritizing local needs, reducing external inputs, and fostering resilience[3][4].

Conclusion:

The most reliable path to biodiversity revival in Central America’s tropical forests involves native species, community leadership, and integrated livelihoods—not corporate-led monocultures. Large-scale, government-driven tree planting can achieve social and economic goals but risks greenwashing if ecological outcomes and transparency are secondary. For genuine regeneration, supporting Indigenous and local community initiatives—backed by sound science and equitable policies—offers the most promising model[1][3][4].